How do the sensory-related factors of an environment impact autistic people’s experiences of public places?

How can we educate people about sensory processing differences and inspire them to make public places more enabling for autistic people?

These are the questions that Sensory Street aims to answer. Our research has shown how public places can be challenging sensory environments for autistic people and what can be changed to make them more accessible and inclusive.

We value co-production, and collaborate with autistic individuals at all stages of the project.

What is Autism?

Around 1 or 2 in every 100 people are autistic (Roman-Urrestarazu et al, 2021; Zeiden et al, 2022), but the actual number is thought to be much higher than this. Rather than being ‘more’ or ‘less’ autistic, each autistic person will have different strengths and challenges that relates to the way they interact with the world around them. People are born autistic and will remain autistic throughout their lives.

You cannot tell someone is autistic by the way they look and autistic people can be any age, gender, or ethnicity. Some individuals may hide or mask their autistic traits more than others, and because of this autism has been called an hidden/invisible disability.

What are sensory processing differences?

Our brains process incoming sensory information, such as sounds, touch, or tastes, as well as internal information, such as if we are hungry. This helps us navigate the world around us.

Autistic people commonly experience differences in the way that they process and respond to sensory information, which can be associated with distressing as well as enjoyable experiences. Studies suggest that 74 – 94% of autistic people experience sensory processing differences (Crane et al., 2009; Kirby et al. 2022; MacLennan et al., 2021).

Some autistic people may respond more to sensory information, meaning that they can find inputs, such as sounds or lights, to be painful and overwhelming. Others may respond less to sensory information, meaning they do not notice sensations such as someone lightly touching their arm or certain smells. Some people may enjoy seeking out certain stimuli, such as preferred smells or tastes.

Although our focus is on autistic experiences, it is important to note that sensory processing differences are not unique to autism, as they are also present across the general population and common in other groups, such as ADHD and Fragile X Syndrome (Ben-Sasson et al., 2009).

Why do we want to learn more about sensory processing differences and public spaces?

In 2021 the UK Government published its national strategy for autistic children, young people and adults: 2021 to 2026, which highlighted that autistic people can feel excluded from public spaces because of the impact of challenging sensory inputs and negative reactions from staff or members of the public. This paper highlights the need for people and businesses to learn and adapt to ensure that autistic people are supported and included within society.

This has also been identified by the autistic community to be a key priority, and in reflection of this, Autistica (the leading UK autism charity which funds and campaigns for research to support autistic people), has recently made it one of their 2030 goals to make public places more accessible for autistic and other neurodivergent people.

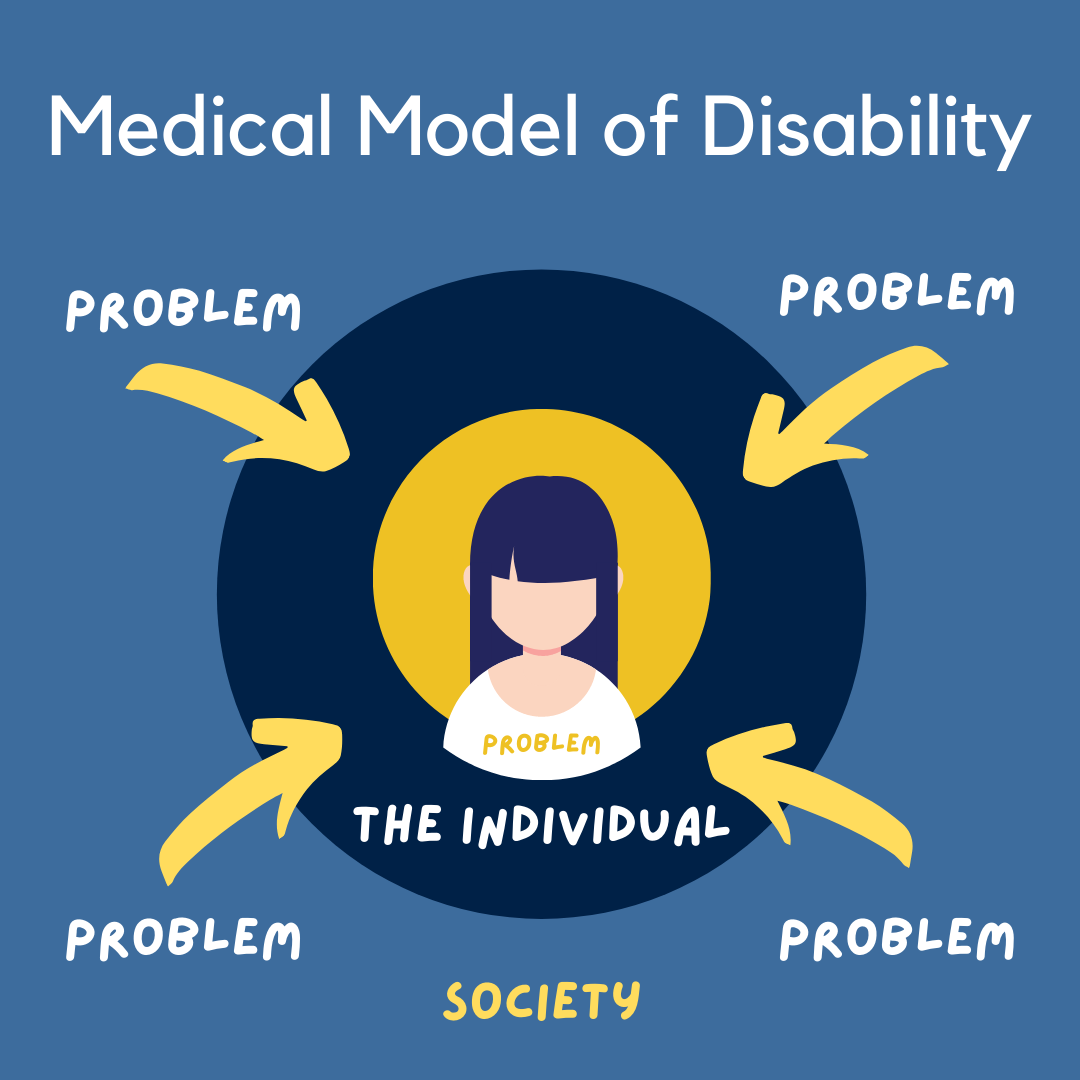

Research to date has often focused on characterising what sensory processing differences are for autistic people, as well as identifying what a person themselves could do differently to cope in more challenging environments. There is limited evidence exploring what environments can do differently to support autistic people and how these can make the world more enabling.

Unlike the medical model, the social model of disability sees an individuals restrictions or challenges as a problem of society rather than the person themselves. By removing barriers, we can help to create equality for everyone, offering people increased independence and control.

Our aim is to understand more about how autistic people are disabled or enabled by sensory environments and provide education to make public places more inclusive and enabling for autistic people.

What have we learnt so far?

You can read about what Sensory Street has done so far in terms of research and public engagement: